|

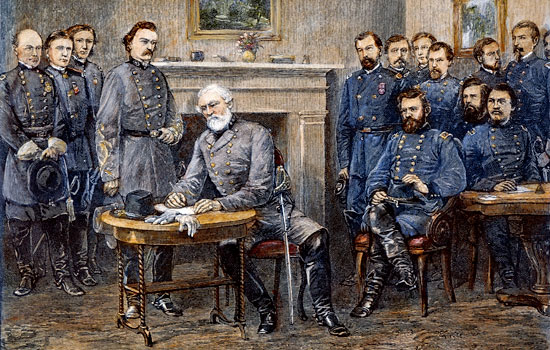

by pragerfan Posted October 14, 2015 Last Updated February 28, 2021 "...The industrial revolution and subsequent mechanization of society came along and made slaves obsolete. It's easy to condemn others for engaging in a practice that you no longer need due to technological advancement. Had you been a southern plantation owner in 1812 America you would most certainly have owned slaves." Response: Slavery is primarily a moral question. Slavery in America was not ended as a consequence of technological innovation. Slavery in America was ended because people who believed slavery was wrong prevailed in war against those who did not. The Biblical writers do not appear to condemn the social institution of slavery directly but rather condemn the cruel and unjust treatment of slaves. This is a subtle but significant distinction. God brought the Hebrews out of the "House of Bondage" (Egypt) because He heard their cries after a "Pharaoh arose who knew not Joseph" (Exodus 1:8). But the Hebrews were also slaves under Pharaohs who remembered Joseph and treated Hebrews justly. After a Pharaoh arose who, as a result of forgetting Joseph, treated the Hebrews cruelly, it was the beginning of the end of slavery in Egypt. It follows that the issue the Pharaoh's cruelty, not the Hebrews' social status as "slaves." In the New Testament, there is no direct repudiation of slavery as an institution; in Galatians 3:28, St. Paul talks about how differences are abolished — there is no male or female, Jew or Greek, slave or free — this explains our new relationship to each other in Christ but it does not morally pronounce on the social institution of slavery. By today's Western, Enlightenment standards, slavery is an evil institution. However, personal liberty as an objective moral good (as expressed by the fathers of the Enlightenment and by the Founding Fathers) seemed to be a little-known concept to the Biblical writers. Authors of the Bible primarily stressed how we treat others, regardless of their station, whatever that station may be. In other words, for the Biblical writers, the sin consists in treating a slave (or anyone else, for that matter) unjustly or cruelly, not in that the person so treated happens to be a slave. But because kidnapping is stealing a human being, those who kidnap and sell people into slavery are liable to judgment, for the commandment is, "Thou shalt not steal." Our modern moral problem with slavery as an institution, regardless of how well slaves may be treated, is that we believe liberty sacrosanct, and therefore we hold that one person cannot own another person as he would own real property, animals, or possessions. But the idea of liberty as sacrosanct originated in the Enlightenment and culminated with the Founding Fathers. The notion that one person cannot own another would likely have puzzled the Biblical writers. It is claimed that "The Bible condones this, the Bible condemns that," and so on. But the reality is that the Bible does none of these things. The Bible is a historical record. The Bible tells us what happened. The Biblical writers, not "The Bible," make moral pronouncements, or record God doing so, such as His giving of the Ten Commandments and the Golden Rule. How we treat our fellow human beings was of paramount importance to the Biblical writers. The authors of the Bible were less concerned with creating revolutions, overthrowing institutions, and establishing new social orders. The Hebrew Prophets emphasized doing justice, loving mercy, and walking humbly with God. Christ's disciples and apostles emphasized faith in the revealed Saviour (John 3:16) and good works springing forth from that faith (St. James). However much it may grate on modern sensibilities, by all accounts the Biblical writers seemed to accept slavery as a fact of life, a life which was too often miserable and short, perhaps the consequence of the fallen state of humanity — but mistreating a slave was a sin. No one, prince or pauper, slave or free, has fully mastered human decency. The Biblical writers do not ask, "how do we get rid of institutions like slavery?" but rather, "given my lot, how do I live a good and moral life?" Micah 6:8 is the Old Testament's answer to that question, and Christ's Golden Rule — do unto others as you would have them do unto you — is the New Testament's answer to that question. While it could be well-argued that the overthrowing of the Egyptians in the Old Testament book of Exodus demonstrates God's antipathy to slavery, the moral and theological impetus and justification for overthrowing slavery as we have known it in the Western world would not be fully developed until many centuries after the New Testament was canonized. The moral justification for final abolition of slavery is rooted in the Protestant Reformation. The chief exponent of the abolition movement was the Englishman William Wilberforce. Slavery in the Western world ended because of military victory: General Robert E. Lee's surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. It's critical to remember that while slavery existed in America (and nearly everywhere else), slavery ended in America.  Surrender of General Lee |

|